I ran across an interesting question recently. If GDP growth has averaged roughly 3% per year for the past 50 years, and inflation also averaged around 3% per year over that span of time, how can stock returns average more than 6%? In other words, if total output (in either real or nominal terms) didn’t grow more than 6% per year, how can the companies that make those products go up in value more than that?

This is a great question, and at first looks like quite a quandary. However, there is at least one key element that has to be added here. First, if the market value of my output goes up 6% due to GDP growth and inflation, but my costs only go up 1% then my profits can go up a lot more, on a percentage basis. Let’s make this more concrete. If my costs are $100 and my revenues are $105, then I have a profit of $5, which was roughly 5% of sales. If my costs then go up to $101, and the value of my outputs goes up to $111, which accounts for a rise in both inflation and output, then my profit rises to $111 – $101 = $10. In this example, profits have doubled and it would not be too surprising to see the stock price go up a lot more than the 6% rise in revenue.

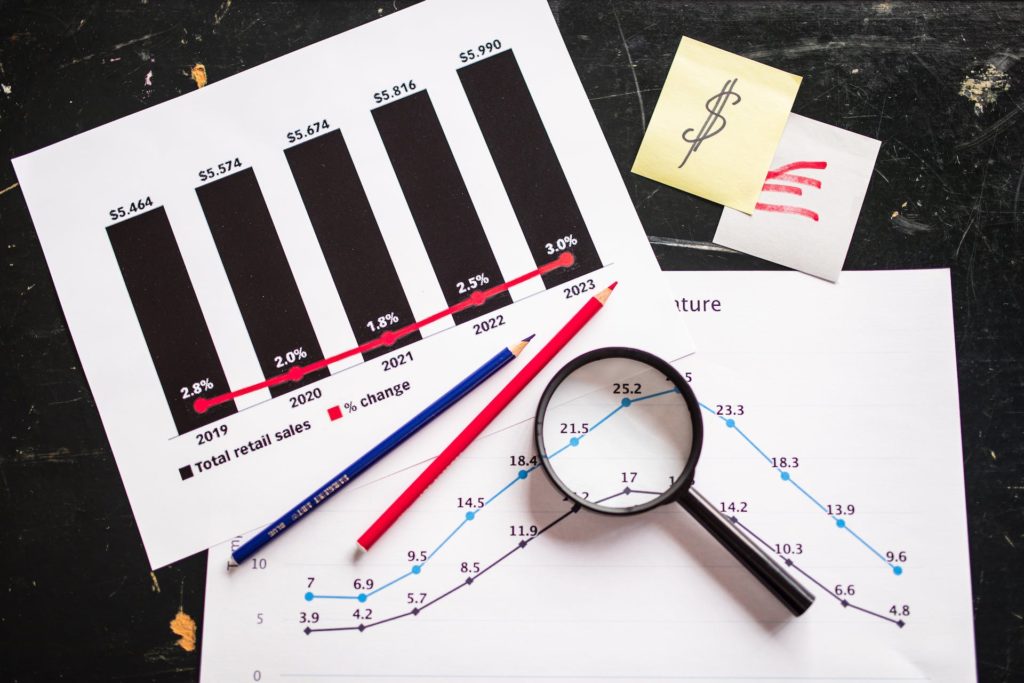

Its natural to ask what any of that has to do with the real world. Check this out. Fifty years ago was 1973. The S&P 500 index at that time was 118 (On Jan 2), and corporate earnings for 1982 were $6.17. At the end of 2022 (50 years later) the S&P 500 stood at 3,840 and annual earnings for that year was $219. By the way, the dividend payments for the S&P 500 also rose from $3.19 in 1972 to $67 in 2022. Just for fun, let’s also note that the Consumer Price Index stood at 43 in 1973 and is at 297 today.

So what you may ask? Look at those figures carefully and you will see that earnings rose by a factor of 219/6.17 = 35 (roughly). What happened to the price of the S&P 500 you ask. It rose by a factor of 3840/118 = 32. As profits goes, so goes the price. By the way, the dividend payments rose by a factor of 66.92/3.19 = 21 while the cost of living as indicated by the CPI rose by a factor of 297/43 = 7. Dividends rise much faster than inflation (which is one reason why I like stocks more than bonds), and this is on top of the appreciation in price which rose much faster than that.

We should also point out that the index fell by 48% from Jan 1973 to 1974. It fell by 49% from March 2000 to October 2002, and it fell by 57% from October 2007 to March 2009. The market level was cut in size by about half on 3 separate occasions and its still 35 times higher than it was in 1973. The US population grew by roughly 50% over that span from 210 million to 333 million, and the productivity of the American worker grew from $26,140 to $60,000 (Yes that was adjusted for inflation.) That productivity growth explains why the value of the output grows much faster than the cost of the inputs driving profits higher. If stock prices are tied to dividend payments and profit levels, and these things rise faster than GDP then stock prices will also rise faster.

This relates to a different notion of efficiency. One side effect of an efficient market is that it allocates capital in a productive way and pays investors to accept the variance in returns that will be produced. When capital is directed to the most productive firms, the value of those firms will grow faster than the rest of the economy. This is a very different notion of efficiency than we spoke about earlier, but it just as important. It’s more like saying that free and fair markets give funds to those likely to do more with it than the average manager. This is another reason that stock prices can grow faster than the economy as a whole. This underscores a fundamental point. Owning a share of stock is NOT owning a macroeconomy, and it is NOT owning a market. It is more like owning a great company. If the profits of those companies grows, then eventually the price will follow, if the market is efficient.

Just for fun, let’s look at a few other “alternative” investments over that same span. The average price of Gold in 1973 was 97.12. As of today (12/6/23) it is $2,000.80. In other words, it rose by a factor of 2000/97 = 20. At first glance you might say that’s not so bad. In actuality, its relatively horrible because the stocks paid dividends along the way and the gold did not. If you invested $10,000 in 1973 in gold you would have roughly $200,000 now. If you invested that same $10,000 in the S&P 500, and reinvested the dividends to buy more shares, you would have roughly $1, 250,000 today. The change in price is only a part of your total returns. Dividends matter A LOT!

Paying investors capital gains and dividends to tolerate the variance in returns, is another thing that efficient markets do. This has to be true for the simple reason that people don’t like variance. They won’t tolerate it if you don’t pay them to do so. Just like your money manager won’t pick stocks for you for free. Efficient markets allocate capital to those set up to make a profit, and it simultaneously pay investors along the way to tolerate the variance that results.